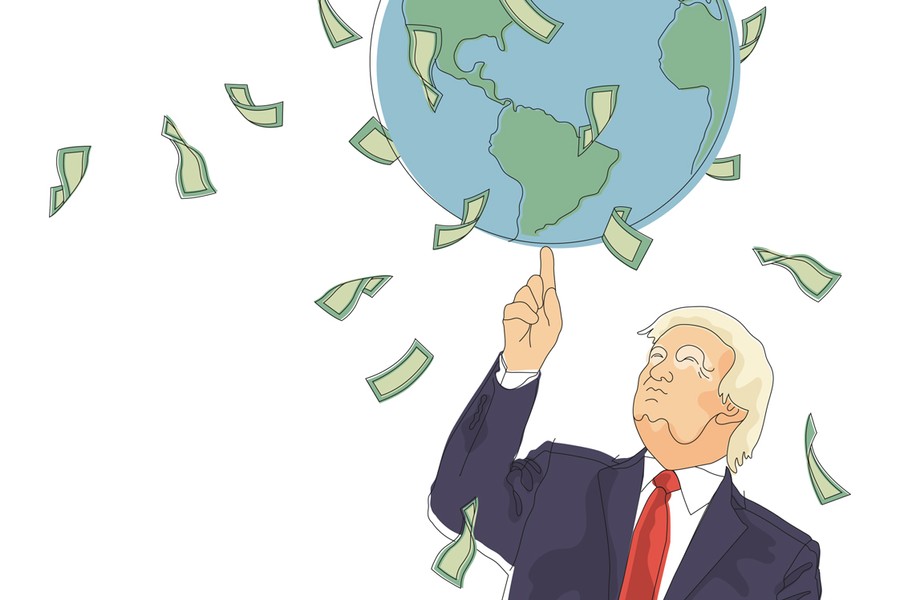

In his second term, President Donald Trump has shifted his economic strategy, moving away from the populist, working class focus that defined his earlier campaigns and embracing Wall Street and the financial sector. This pivot marks a significant change in both policy and rhetoric, with wide-ranging implications for the US economy and financial markets.

Trump’s initial appeal was rooted in addressing the economic dislocation caused by globalisation, particularly after China joined the World Trade Organisation in 2001. Over the years, US GDP composition has changed: corporate profits have increased by 7% as a share of national income, while labour income has declined by 5%. This shift fuelled Trump’s earlier promises to revive domestic manufacturing, renegotiate trade deals, and tackle the ‘K-shaped’ economy—characterised by growing inequality between the wealthy and working class.

However, the realities of governance in his second term—especially post-Liberation Day volatility and concerns over the Treasury market—have led Trump to court Wall Street more directly. His administration has adopted deregulatory policies, including relaxed oversight by the Securities and Exchange Commission and has passed legislation making the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act permanent via the One Big Beautiful Bill Act. The Act will deliver tax cuts of US$4.5trn over ten years, with spending cuts of around US$1.2bn centred around Medicaid, food aid, welfare and clean energy. This type of deficit spending is usually bullish for equities, which have hit record highs under the banner of “unleashing American innovation”.

Underperformance of the US economy versus the rest of the world over the balance of 2025 is likely, as the effects of tariffs feed through.

A key upcoming change is the expected departure of Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell in May 2026 (but the White House is keen to announce his replacement as early as possible). With federal debt interest burdens rising and the debt-to-GDP ratio projected to reach 140% in the 2030s, Trump has criticised the Fed’s reluctance to cut rates, with the implication that fiscal pressures may increasingly influence monetary policy. While on the one hand this is a clear assault on the independence of the US central bank, on the other hand, there seems to be a desire on the part of the Trump administration to challenge legacy academic theories and institutional groupthink at the Fed that hindered its decision-making in recent years.

Meanwhile, the Treasury is issuing more short-term bills—now 21% of outstanding debt—rather than long-dated bonds. This boosts market liquidity and supports risk assets. In this environment, lower Fed Funds rates would benefit both the Treasury and financial markets more broadly.

Despite these tensions, markets have adapted. There’s growing acceptance of inflation closer to 3%, even as the Fed maintains its 2% target. However, the bond market vigilantes are always circling, and if sticky inflation prompts them to drive up long-term yields in a disorderly fashion, the Fed may intervene using its balance sheet, a move which could ultimately evolve toward yield curve control.

The front-loading of activity ahead of the implementation of tariffs and Trump’s (admittedly haphazard) de-escalation of the trade war have seen economic activity data holding up generally better than anticipated. However, it is only a matter of time before trade policy begins to weigh on US hiring and investment. As a result, we expect weak US economic data in the second half of 2025, with mounting pressure on the Fed to reinitiate the rate-cutting cycle it began in 2024. Looking ahead to the 2026 US Midterm elections, we expect fiscal, monetary, and regulatory policies to be increasingly aligned to support financial markets, especially equities. The US Dollar, however, is likely to continue its downward trajectory as the effects of the budget and current account deficits combine with the prospects for reduced Fed independence and less appetite on the part of central banks to hold the US currency.

Notwithstanding the recent impressive recovery in US equities after their sharp correction in April, year-to-date equity returns have been much broader by region and sector than in the recent past, and this is something we anticipate will remain the case for the rest of the year. This reflects the likelihood of significant underperformance of the US economy versus the rest of the world over the balance of 2025 as the effects of tariffs feed through into US activity data. In addition, policy reflation outside of the US, notably in Europe, the UK and China, has increased investor appetite for a slightly less US-centric equity allocation. Finally, the prospects for further US Dollar weakness will erode the US equity returns for non-US investors, reversing the trend of the last decade.